This article was originally published by Votebeat, a nonprofit news organization covering local election administration and voting access.

The group of Navajo speakers gathered in Flagstaff were deep into translating the pages stacked in front of them when they began deliberating over how to best describe fentanyl.

It wouldn’t be a straight translation — almost nothing is, from English to Navajo. But these county and state election officials, charged with translating Arizona’s long and complex ballot for a key group of voters on the Navajo Nation, would try their best to get it right.

“Not azee’,” someone said. “Azee’ is medicine. It’s to heal.”

They looked down at the English text: “Criminalizes selling fentanyl that causes the death of a person.”

Azee’, they decided, gave the wrong impression. The group would need new wording, and quickly.

This was just a single sentence, a small piece of just one of the 13 propositions set to appear on Arizona’s November ballot. By the end of the day, the group had to finish translating all of them into Navajo. Because Navajo is a historically oral language and many who speak it cannot read it, the goal was to come up with a translation that voters who are not proficient in English could listen to at the polls.

Several of the proposals on the ballot are hotly contested, from abortion rights to open primary elections. While the English language used to describe those propositions has been the subject of debate in the press, public, and courts, the translations into Navajo and other languages receive little attention or public scrutiny, even though they are covered by federal law.

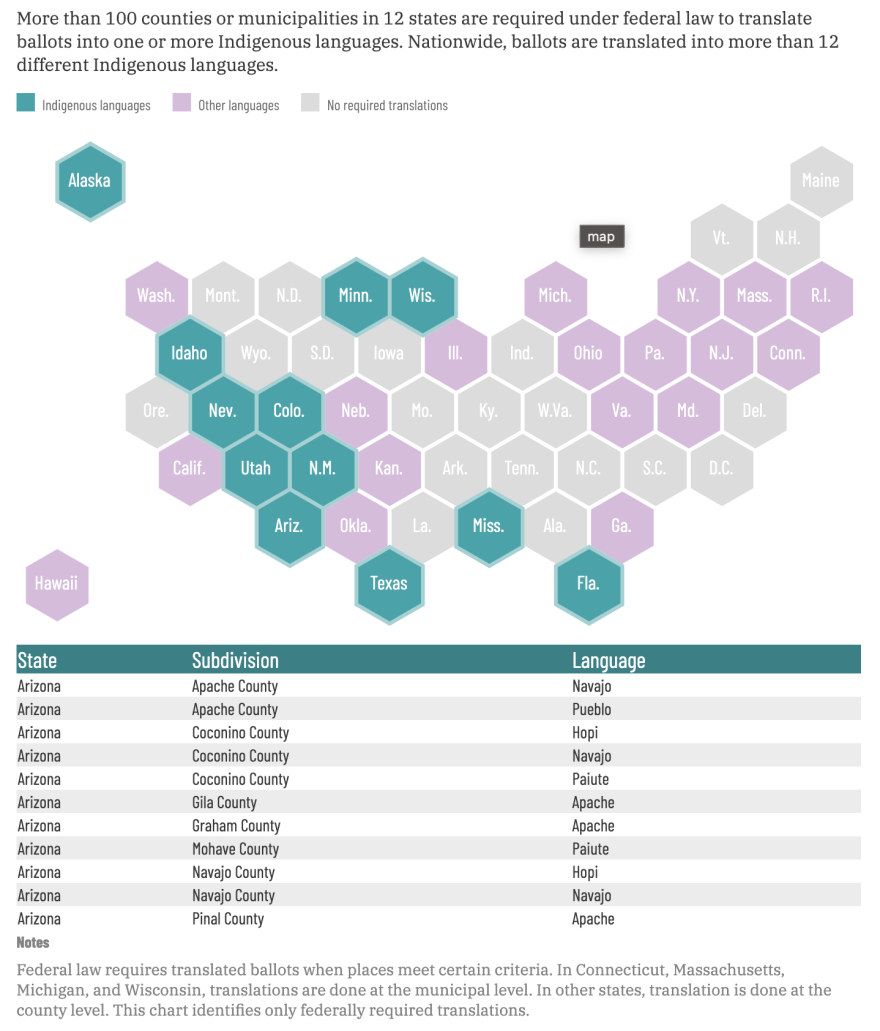

Section 203 of the federal Voting Rights Act requires places around the country to translate election information into specific languages if they have significant numbers of residents who share a common language and don’t understand English well, or if they meet other criteria. It’s a challenge to do these translations, and do them correctly, especially for counties such as those in Arizona that must translate historically oral languages.

Where federal law requires ballots to be translated into Indigenous languages

Over the years, courts in Arizona and elsewhere in the country have found that election officials haven’t done enough for such voters and have ordered them to do more.

Multiple Arizona counties fall under the law, including seven counties subject to Native language requirements. Some counties are required to translate into multiple Native languages, including Navajo, Hopi, and Apache. Some exceptions have been granted to counties for Paiute and Pueblo translation requirements, officials said.

The translation work in Arizona this year largely took place in private meetings, such as the Navajo gathering, held over two days at the Coconino County Elections Center.

The public’s view into the translation process is limited. A Votebeat reporter accompanied by a videographer obtained advance permission from the Arizona Secretary of State’s Office to sit in on the second day of the Navajo meeting, and were allowed to watch, after briefly being barred from attending.

The meeting provided a window into the complexity of the process, as well as the limits of Arizona’s efforts to make elections fully accessible to Navajo speakers.

Navajo vote is pivotal in Arizona

Navajo-speaking voters are a closely watched group. High turnout from the Navajo Nation — which sweeps across the entire northeast portion of Arizona before stretching into Utah, Colorado and New Mexico — has heavily influenced the outcome of some statewide elections. In 2020, Indigenous voters were a critical voting bloc that helped decide the presidential election in favor of Joe Biden in this swing state, and their choices could determine the fate of high-profile ballot measures this year.

Around 71,000 Arizonans of voting age speak Navajo, and about 1 in 10 of them aren’t fluent in English, according to a Votebeat analysis of 2022 U.S. Census estimates.

Navajo voters who don’t speak English well may get less information this election than voters who do. A 2019 settlement agreement between the Arizona Secretary of State’s Office and the Navajo Nation requires the office to use certified Navajo translators to “coordinate and make available” a translation of all text describing each proposition that is included within each election’s publicity pamphlet, an English-language guide the secretary of state sends to all voters before each

The full text in that guide includes not only the text of the ballot measure as it appears on the ballot — which has to be very short, under state law — but also a full separate description of what a “yes” or “no” vote on the measure would mean. Those yes/no descriptions are also provided to voters in their mail ballot packet, or as a handout at the polls.

But attendees at the Navajo translation meeting discussed only the proposition text on the ballot, not the additional yes/no descriptions. Secretary of State’s Office spokesperson JP Martin said the counties were provided a translation of the yes/no section. It’s unclear whether voters will be provided with a uniform translation in the form of an audio recording.

Asked why the Navajo meetings were closed to the public, Martin wrote in an emailed response that it “minimized disruptions and allow interpreters to focus on their work.”

Leonard Gorman, the executive director of the Office of the Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission, who is Diné, the word used by Navajo people to describe themselves, said he has repeatedly found problems with the state translations over the years. He wasn’t permitted to attend the Navajo translation meetings.

Navajo-speaking voters “will not understand what they are voting for” if the translation is flawed, Gorman said. “That is not what Section 203 is about.”

The Navajo Nation Office of the President did not receive an invitation to the meeting, either, according to George Hardeen, a spokesperson.

Sensitivity over abortion complicates translation work

This year, the Arizona’s Secretary of State’s Office hired translators and helped develop uniform ballot translations for Spanish, Navajo, and Hopi, but not for Apache. The three counties that must translate into Apache will handle the requirement on their own.

The Navajo translation is supposed to be used to train bilingual poll workers on the reservation. An audio recording of the final translation is also available on the accessible voting device at each polling location, so voters can listen to it if they choose.

The careful conversations and sensitivity to language throughout the Navajo translation meeting hinted at the complications inherent in translating from English to Navajo. Translating one English word often requires creating a multi-word Navajo phrase that aims to capture its meaning. There are typically multiple ways to translate something, especially terms commonly used in elections.

The culturally sensitive topics on the ballot this year made agreeing on the proper Navajo translation even more complex, according to some of the county officials who participated.

Take Proposition 139, which would guarantee abortion rights for Arizona residents. Navajo culture traditionally does not approve of abortions, said Melvatha Chee, an assistant professor of linguistics at the University of New Mexico and director of its Navajo language program.

Some interpreters will intentionally soften language on topics such as abortion when translating into Navajo, in an effort to avoid offending anyone, Chee said. Chee, who is Diné and has helped translate ballots for New Mexico but wasn’t part of the Arizona discussions, said that could mislead voters about what the proposed change to state law would do.

Chee listened to a recording provided by Votebeat of the draft form of the Navajo translation of the abortion proposition discussed at the meeting. In it, the word “abortion,” which doesn’t have a direct counterpart in Navajo, was translated to awéé' t’óó átsą́ haal’eełjí.

Chee said she was concerned Navajo voters could believe the phrase referred to a miscarriage rather than an abortion.

“So this word, átsą́ haal’eełjí, is flushed out of the belly, like it flowed out like liquid. That is what that means. And that describes a miscarriage,” Chee said. “That is not an abortion. An abortion is, someone goes in there, and they remove a fetus. So, right away, you can tell that cultural sensitivity, that cultural aspect of that, is already showing up in the first four words of this translation.”

She said changing the verb construction would better convey the idea that a deliberate action was causing the fetus to come out.

She said that she frequently hears from Navajo interpreters that they don’t want to use certain language.

Karen Shupla, who is Hopi and is the Coconino County Recorder’s Office Hopi translator, said her own personal view on abortion meant she had a “mental block” as she tried to participate in the Navajo translation meeting, and she had to set aside her own feelings.

“I had to be open,” she said. “I can’t be personal on these propositions.”

Isaura Nez, Navajo County’s voter outreach coordinator, who is Diné, said there were also sensitive questions when translating Proposition 313, which would change the punishment for child sex trafficking. She said she didn’t believe the description of sex trafficking should use the word for rape.

“We had to go back and revisit that one,” she said. “We went round and round with it, because saying rape was a lot harsher, I thought.”

Translation gaps persist despite legal settlements

County officials came to the meeting with a Navajo language elections glossary and dozens of pages of handwritten notes, and debated extensively even over words as anodyne as “border” or “economic opportunity.”

After the meeting, Shupla stressed how important it was to get the translation exactly right. But despite the group’s diligence, there’s no guarantee that voters and their advocates will be satisfied with the outcome.

Since at least 2016, Gorman, of the Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission, has been monitoring the language assistance offered to Navajo voters. In all those years, he said, he has not issued a positive report.

In 2018, just after the November midterm election, the Navajo Nation filed a sweeping lawsuit against the state and Apache, Coconino, and Navajo counties, claiming, among other things, that the counties did not provide sufficient Navajo translation resources.

The counties and state settled the case, each signing separate agreements with the Navajo Nation. Navajo County agreed to continue providing translators at each polling place on the Navajo Nation, to make sure at least one person is available to translate at early voting sites, and to continue to provide an interpreter’s guide. The county also must use a trained translator or interpreter to train poll workers on providing effective language assistance to Navajo-speaking voters.

The Secretary of State’s Office believes those agreements have led to improved oral translation services at voting sites. The agreements have “guided more structured and proactive approaches, ensuring compliance and addressing potential issues before they arise,” Martin told Votebeat.

The state’s settlement in the case requires a Navajo translation of the full proposition language in the pamphlet, including the text of the ballot measures as they appear on the ballot, as well as the yes/no language.

During the August meeting, Nez from Navajo County and Shupla from Coconino County both told Colleen Connor, policy director in the Secretary of State’s Office, that they were concerned that they weren’t discussing the translation for the yes/no language, which they said contained important details. That part will be handed to voters at the polls in English.

Shupla told Connor that just providing the ballot translation, without the yes/no section “could be misleading,” and she worried the counties would get backlash from voters. “I can hear one person already saying, ‘Why didn’t you provide us the full information? You misled us,’” Shupla said.

Connor, who attended the meeting via video, responded to their concerns by saying that she agreed that the separate language provides a better explanation of all components of the ballot measure, but did not explain why they were not discussing the translation.

Coconino County Recorder Patty Hansen said in an email after the meeting that the county’s staff will “make sure that the interpreters are trained so that the voter will understand what the question is and what a yes and no vote means.

“It may not be done in the same manner as what is on the English language ballot,” she added.

Allison Neswood, a lawyer for the Native American Rights Fund who litigates Section 203 violations, said she believes that, for historically unwritten languages such as Navajo, the law requires election officials to orally translate into Navajo any election material available in English.

Neswood said that if Arizona wants to allow for “meaningful participation” — the standard set in the federal law — it should be translating the full pamphlet. She said an exception in the law that election officials do not have to offer a written translation for historically unwritten languages has allowed counties “to get out of the full scope of the program.”

Neswood pointed to a 2013 case in Alaska, where the Native American Rights Fund represented Alaska Native groups and residents in a lawsuit claiming the state wasn’t honoring an agreement to translate election information into Alaska Native languages.

In that case, Neswood said, the plaintiffs pointed out how English voters were offered a pamphlet more than 100 pages long explaining the candidates and ballot initiatives, while speakers of Alaska Native languages received just one page stating where and when to vote.

“The judge looked at that and said this is completely wrong,” she said. The judge then ordered that the state translate the entire pamphlet, and all other election material offered in English.

Asked to respond to the idea that Arizona should be translating more materials, Martin, the Secretary of State’s Office spokesperson, said the state is committed to seeing that all voters covered by Section 203 receive the assistance they deserve.

“When feasible and beneficial for the community, written translations of voter education and informational materials are also made available,” he wrote.

How could language assistance improve?

Gorman, from the Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission, said in an interview that the settlement agreements have not led to improved language assistance for Navajo voters.

After the November 2022 election, he sharply criticized the translation provided at the polls, in an email that was forwarded to the Secretary of State’s Office. In the email, which Votebeat obtained through a public records request, Gorman said he had trouble understanding the translation, even though he is proficient in both Navajo and English.

That was particularly the case when he tried listening to the audio recording on the device at his polling place, he wrote. For example, he wrote, the instructions explaining how many candidates a voter can choose from were translated in Navajo as something like “there are two,” with no further context.

Not many voters actually rely on that recording, according to county officials and Native voting advocates. Nez, in Navajo County, said it takes a long time to listen to the whole thing. She predicts that will especially be true this November, since the ballot is unusually long.

Older Navajo voters, typically referred to as elders, are more likely to need help at the polls, Nez said. Many of them bring family to the polls to help them, she said, or call on the translators.

That reinforces findings in the U.S. Census data, which shows that nearly all of the Navajo speakers in the state who don’t speak any English are over the age of 65.

“A lot of them are going to say, ‘I don’t want to do this, whatever, just vote ‘no,’ or just vote ‘yes,’” Nez said.

Neswood said she believes a close look at how counties around the country are providing language assistance would show that most of them are not meeting federal law, “especially in the Native language context,” though she acknowledged that doing so is challenging.

She said she believes Congress needs to change Section 203 so that Indigenous voters receive adequate language assistance. For example, she said, traditionally spoken languages should be treated the same under the law as written languages, but a tribe could opt out of a written translation.

Neswood also recommends requiring written translations for use by translators who will be helping voters. And she believes that election material provided by the secretary of state should be explicitly covered by translation requirements, along with county material and ballots.

“I don’t think that’s clear enough in statute,” she said.

Chee, the linguistics professor, said that counties should hire more than one professional translator, so that they can review one another’s work. The translations they use should include all proper context and be as thorough as possible.

Otherwise, Chee said, she imagines a scenario where an elderly Navajo voter might ask a question, “and before you know it, the poll worker might be telling a story that might not be true.”

Votebeat data journalists Kae Petrin and Thomas Wilburn contributed. Video: Shannon Spencer, Elaine Cromie and Jen Fifield.

Jen Fifield is a reporter for Votebeat based in Arizona. Contact Jen at jfifield@votebeat.org.

Votebeat is a nonprofit news organization covering local election integrity and voting access. Sign up for their newsletters here.