This story was originally published in The Colorado Sun.

The omicron variant is rapidly gaining steam in Colorado, now accounting for potentially as much as half of all new infections, the state’s top epidemiologist said Wednesday.

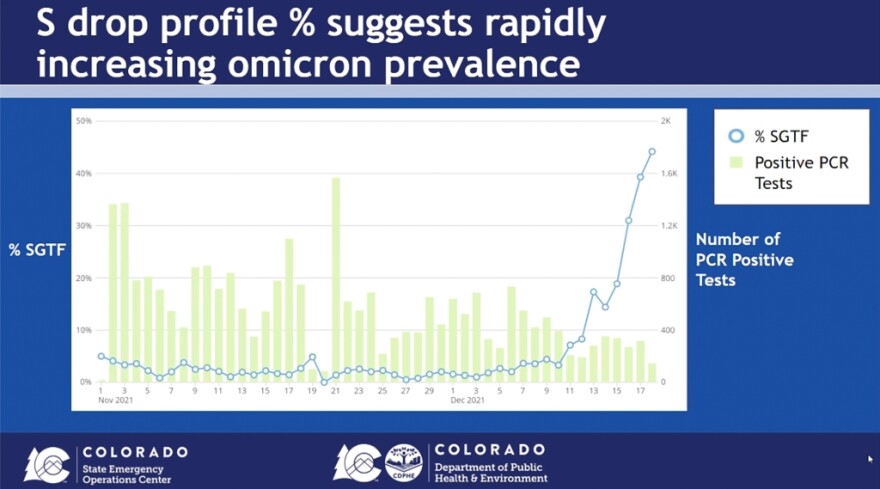

After several weeks of decline, COVID cases in Colorado have begun to rise again – though they are still about 50% below where they were in early November. Dr. Rachel Herlihy said genetic sequencing work is still being done to confirm that omicron is driving the rise in cases. But she said the state laboratory is now finding a specific calling card of the variant in close to half of the tests it is running.

Signs of the variant have also been detected in all 21 wastewater systems that participate in a state program to track COVID through sewage, indicating that the variant isn’t isolated to just a handful of places.

“At this point, we do believe that omicron is widespread across the state and there is likely local transmission occurring in many of our communities,” Herlihy said.

Herlihy’s comments show just how fast the variant may be moving and how quickly officials’ understanding of the situation is changing.

Just one day prior, the state published data showing that omicron was estimated to be responsible for about 10% of Colorado’s COVID infections during the week that began Dec. 12. Also on Tuesday, Gov. Jared Polis said, “It is still not the predominant strain in Colorado.”

“At this point, if you get COVID,” Polis said, “the chances are it is still the delta variant in Colorado.”

But some of Colorado’s mountain resort communities are getting hammered with new cases, and public health leaders there have become increasingly vocal about the likelihood that omicron is to blame.

Summit County on Friday recorded four new COVID cases. On Tuesday morning, the county received word of 112 new positive tests reported overnight, per a county news release.

“The emergence of the omicron variant poses yet another new challenge to all of us,” Lee Boyles, the CEO of Centura St. Anthony Summit Medical Center, said in a statement. “The speed at which omicron appears to spread and become dangerous in the body, including among the vaccinated but not boosted, is concerning.”

On Monday, Eagle County reported 139 new COVID cases, prompting the county board of health to hastily call a meeting Wednesday to institute an indoor mask mandate.

“It’s absolutely driving it, because the rapid increase in acceleration is like nothing we have ever seen, really,” Chris Lindley, Vail Health’s chief population health officer, told the Vail Daily.

Officials don’t know for sure that these new cases are all omicron – the task of conducting genetic sequencing on them to confirm the variant’s presence can take weeks. But omicron produces a telltale result in a standard PCR coronavirus test that gives officials a good idea of what they’re dealing with.

The result is called an S-drop profile or an S gene target failure. Because omicron’s spike protein is so heavily mutated, standard coronavirus tests don’t pick up on the spike, though they do find other markers in the virus’s genetic code.

The rapid increase in the state laboratory’s results with an S-drop profile prompted Herlihy’s statement Wednesday that as many as half of all new cases in Colorado are being caused by omicron. The delta variant does not produce an S-drop profile, though an earlier variant did. As recently as the first week of December, Colorado was seeing only a handful of tests with an S-drop profile per day.

Herlihy said the earliest known cases of omicron in Colorado were associated with people who had traveled elsewhere, but that is no longer true. What’s more, the state’s contact-tracing is showing that people who had close contact with someone infected with omicron are twice as likely to come down sick as those who had close contact with someone infected with the delta variant.

Herlihy said she is hopeful that Colorado’s booster-shot campaign – nearly half of those eligible for a booster have received one, Polis said Tuesday – will help blunt omicron’s spread. Studies have shown that a third dose of the Pfizer or Moderna vaccines takes much of the sting out of omicron.

She also said Colorado’s recent wave of delta-caused infections may also help because a lot of people may now be walking around with recently acquired natural immunity.

But, those are just hopes, she said. No one really knows what will happen next, especially since the research on whether omicron is more or less severe than previous variants is still a work in progress, though early signs are promising. Colorado may be days aware from experiencing the kind of near-vertical case waves currently seen in other U.S. states.

“I think it is quite possible,” Herlihy said, “that we’re going to follow the trends we’re seeing in some large cities on the East Coast and states on the East Coast.”