On a sunny Wednesday morning, 40 tourists visited Balcony House, one of Mesa Verde’s ancient Puebloan cliff dwellings.

Visitors shimmied through tiny openings in sandstone architecture and climbed up a 40-foot ladder.

The tour guide was Jordan Fragua, a 21-year-old Pueblo of Picaris and Ohkay Owingeh man. His job allows him to combine park interpretation, public speaking, and his cultural upbringing.

“It's really rewarding,” said Fragua. “Different rangers will say, ‘This is a sacred spot,’ and they mean it in good faith, but for me, it is an actual sacred site.”

Fragua is part of Mesa Verde’s new Indigenous Ranger Internship program, which aims to include young Indigenous people from the Four Corners region in the storytelling at the park.

For decades, Native Americans have criticized the National Park Service for excluding Indigenous perspectives. According to the National Parks Conservation Association, only 2.5% of Park Service employees identify as Native American or Alaska Native.

Fragua offers a perspective that other park rangers cannot — he includes his Pueblo culture in his tours. He tells the tourists that Pueblo people like himself visit the cliff dwellings daily to connect with and honor their ancestors.

“Every single day this summer, there's been at least one Pueblo come back here to leave some sort of offering behind for the people that lived here, come back all the time to remember where we come from,” said Fragua.

In the early years at Mesa Verde, the agency presented offensive narratives and struggled to preserve cultural sites. In recent years, the park changed museum exhibits and publications to tell a more accurate story of the Indigenous people who lived there.

Kristy Sholly is the Chief of Interpretation and Visitor Services at Mesa Verde. She said that two years ago, the park reviewed exhibits in its Chapin Mesa Archeological Museum.

“We had to have the hard conversation at the park about certain displays that were considered offensive or unwelcoming to the tribal communities. A lot of those exhibits have been on display for almost 100 years,” said Sholly.

One of the most controversial changes was a diorama depicting Native peoples having the physical features of prehistoric ancestors, not modern humans.

“Rather than displaying them just as tribal community members, they were displayed as Neanderthal-age people,” explained Sholly.

“Which goes back many, many millions of years. The tribal community members told us that there would be no context in which displaying these exhibits would be appropriate.”

I asked Sholly whether, intentionally or not, the dominance of white employees has led to the exclusion of Indigenous perspectives at the park.

“I'm not in a place to judge history,” said Sholly. “And I think that it's a bit of a leading question. I think that all of us are doing our best. And we're trying to make progress. But again, we're learning along the way. I feel better today that our tribal community members have a lot of voice in the interpretation of this place. If 100 years out, people are looking back. I don't know what they would say about what we're doing today.”

This summer, there were five Indigenous park rangers giving tours at Mesa Verde. Four were interns. Cecilia Shields, a Pueblo of Picaris woman, is the one permanent employee. She’s also Fragua’s mother.

“We should definitely always have Indigenous peoples here to lead tours and to be part of the process,” said Shields.

Soon, Shields will be the only Native American giving tours at Mesa Verde. The last intern leaves the park in November.

In her work as a ranger, she’s reckoned with the realities of historic preservation here at Mesa Verde.

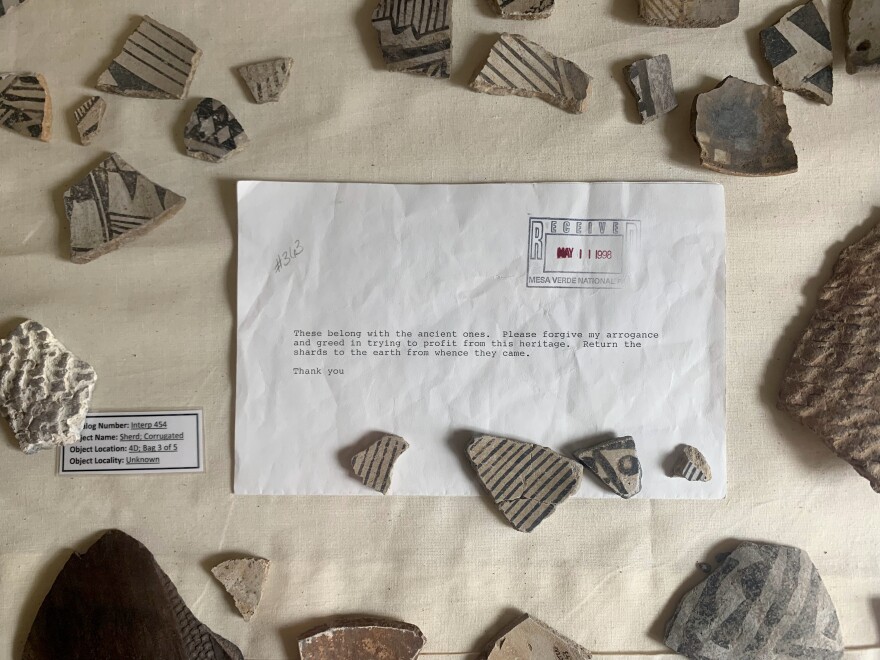

“There are some things that were hard to understand,” said Shields. “For us, those things should all be returned and allowed to have their cycle and be returned to Earth, but just knowing how many artifacts are in collections in dark rooms and in boxes that never get to see the light, at what point do you have enough potsherds?”

Cecilia Shields said she’s comfortable being both a Park Service employee and a Native American woman with ancestral connections to the area.

“A long time ago, I found my peace with it,” said Shields. “The mission of the National Park Service is to preserve and protect these special places for future generations. I feel that being a park ranger is a good thing, but I wish there were more of us. Sometimes, the only way they'll listen is if I'm wearing the flat hat and the green and gray uniform.”