This story was originally published by The Colorado Sun at 4:01 AM on July 7, 2023.

Colorado is drought-free for the first time in four years — a rare reprieve for a state in the middle of a megadrought.

According to researchers, the hot and dry conditions in the southwestern United States since 2000 account for the driest period on record over the past 1,200 years. Colorado itself has only had short blips of time over the past 22 years when drought conditions disappeared completely across the entire state.

But this year’s snow, rain and hail have doused the state so well that some areas of metro Denver are beating rainy Seattle for year-to-date precipitation. This week, for the first time since mid-July 2019, Colorado is all clear of drought, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.

“It’s a big deal in terms of, we don’t have to worry about impacts from drought right now,” said Becky Bolinger, Colorado’s assistant state climatologist. “It’s very uncommon for us to be in the summer months and not have drought anywhere in the state.”

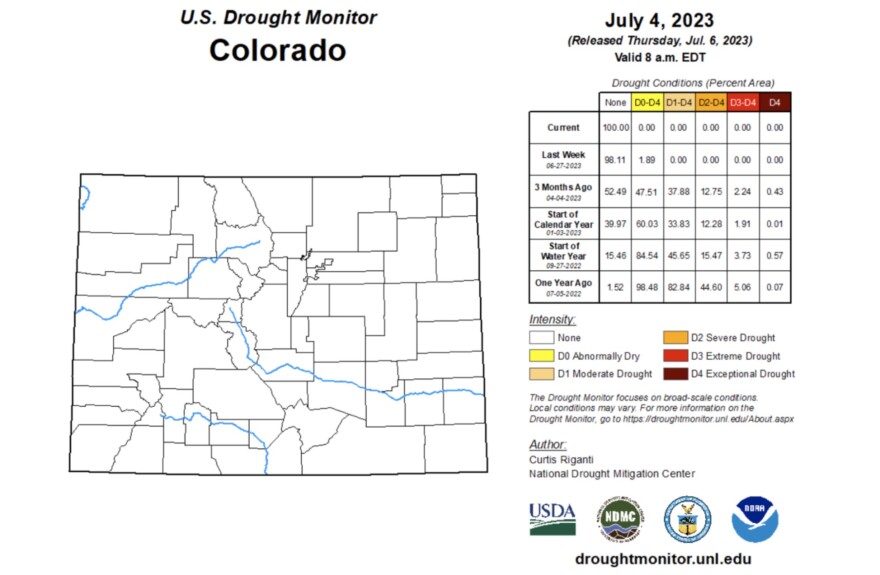

The Drought Monitor’s map of Colorado typically shows bands of yellow, orange and reds across the state, indicating the location and severity of drought and near-drought conditions statewide.

The Drought Monitor compiles environmental indicators — like precipitation, streamflow, reservoir levels, temperatures and soil moisture — into maps and data used by federal agencies, state, local, tribal and regional decision-makers. It’s the top source of information on drought nationwide, Bolinger said.

As of Thursday, Colorado’s drought map is entirely clear.

“Overall, what we’re seeing is that the wet pattern that we’ve been in, the excellent snowpack we’ve had all contributed to making us completely drought-free now,” Bolinger said.

Not only did the state end winter with a higher-than-average snowpack, parts of Colorado have received near-record precipitation.

For Denver, May was the fourth wettest May on record with about 5.53 inches of rain, according to National Weather Service data compiled by the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. In fact, Denver International Airport, where Denver’s official weather measurements are recorded, reported more precipitation than Seattle-Tacoma International Airport since Jan. 1. Denver saw about 15.2 inches compared with Seattle’s 14 inches. (That’s about 6 inches less than Seattle’s normal year-to-date precipitation, according to the weather service.)

Some areas around Castle Rock in Douglas County have gotten 30 inches of precipitation. The area normally gets 15 to 20 inches of precipitation for the entire year, Bolinger said.

Western Colorado is lagging behind its normal precipitation, based on historical data from 1991 to 2020. So far it has received 50% to 75% of its 30-year normal from April to June, according to Lucas Boyer, meteorologist at the National Weather Service.

Southeastern Colorado, the only region with lower-than-average snowpack this year, has seen enough moisture and cooler temperatures to make up for the lack of snow, Bolinger said.

However, Bolinger said statewide precipitation in June looked to be about 1.5 inches above average. As of May, much of eastern Colorado was seeing higher than average precipitation.

A glance back at the state’s drought over the past 22 years, however, shows how consistently these moments of reprieve are followed by more severe drought conditions, according to Drought Monitor data.

There were short spans of time — mere weeks in most cases or less — where most of the state was all or nearly clear of drought in 2000, 2001, 2009, 2015 and 2019.

But those periods were followed by the complete opposite conditions in most cases. Most of the state, 80% to 100%, was in or near drought conditions, including exceptionally severe drought, from early 2002 to late 2004, mid-2012 to mid-2013, and mid-2020 to mid-2021, according to Drought Monitor data.

For most of the 22-year drought period, about 20% to 60% of the state was experiencing drought or near-drought conditions.

“This isn’t something that will last forever, and we’re keeping our eyes out for where is the development of the next drought going to be? Because it’s not a matter of if, but when,” Bolinger said.

This year’s break from drought means crops are benefitting from good snowpack and rain. In some cases, the crops are running behind schedule because they haven’t had enough sun and warmth. The hail, however, has been a problem, particularly smaller, wind-driven hail that damages every stalk of wheat, corn and alfalfa it hits, Bolinger said.

Across the Front Range, most municipalities are drawing less irrigation water because residents are relying on rain, rather than sprinklers, for their lawns and landscaping.

Although there are wildfires around the state, they’re easier to contain and control because of the wetter conditions than the devastating wildfires in dry years, she said.

As the winter snowpack melts, dry soils can suck up runoff before it reaches streams and rivers. This year, soil moisture is in decent shape across the state, Bolinger said.

If soils are still in good condition come fall, it will be a better start for the next snow season and it can help recharge deeper water tables, she said.

And reservoirs, the state’s water storage system, are recovering. Over the past three years, winters have brought less-than-average snowfall to Colorado’s mountaintops, which has a trickle effect on the entire Colorado River system, which spans seven southwestern states and part of Mexico. That means lower rivers, drier soils and lower reservoirs, Bolinger said.

This year, Colorado’s reservoirs are rapidly refilling. Blue Mesa, the state’s largest reservoir, went from a near-record low last summer to near capacity this summer. Dillon Reservoir, which feeds Denver’s water supply, was at 101% of its capacity Thursday.

“The difference between what we’ve experienced, especially if you look at a year like 2020 or 2021, it’s the difference between night and day,” Bolinger said. “The conditions we’re currently experiencing are completely opposite of that.”