This is the first in a five-part series for The Colorado Dream: Ending the Hate State. The stories in this series are part of the KUNC podcast The Colorado Dream, airing on Mondays beginning October 7. The podcast is available for download wherever you may listen to podcasts and on KUNC.org.

There’s no better window into the frontlines of Colorado’s long and bumpy fight to secure LGBTQ+ rights than Glenda Russell’s cluttered research room in Boulder.

Here, Coloradans don’t just learn about the setbacks and victories.

They can feel them as Glenda opens her files and reads her detailed notes, which include somber testimony how anti- LGBTQ+ ballot measures and rhetoric has impacted Coloradans.

“Gay people were objectified and talked about in all kinds of ways. A lot of lies were promulgated,” Russell said.

Russell brings this history to life in ways that few others can. As a lesbian, she has had a personal stake in it. She’s also a psychologist who did groundbreaking studies about the mental impacts of these key events.

Her quest to preserve and become a part of this history started in 1974. She was sitting in the Boulder City Council chambers when they were debating whether to become the first city in Colorado to ban workplace discrimination based on sexual orientation.

It was a heated debate.

“There were 400 people at the hearing. It went back and forth between pro and con on the issue and I was aware ‘Oh my gosh, this is really a history in the making,” Russell said.

Efforts to protect LGBTQ+ people from discrimination would eventually land Colorado on the frontlines of one of the biggest court cases in queer history.

As the years ticked by, Russell continued documenting key moments in this bumpy fight for social equality. She squirreled away newspaper clippings and more of her notes.

Then, in the early 1990s, the history took a dark turn.

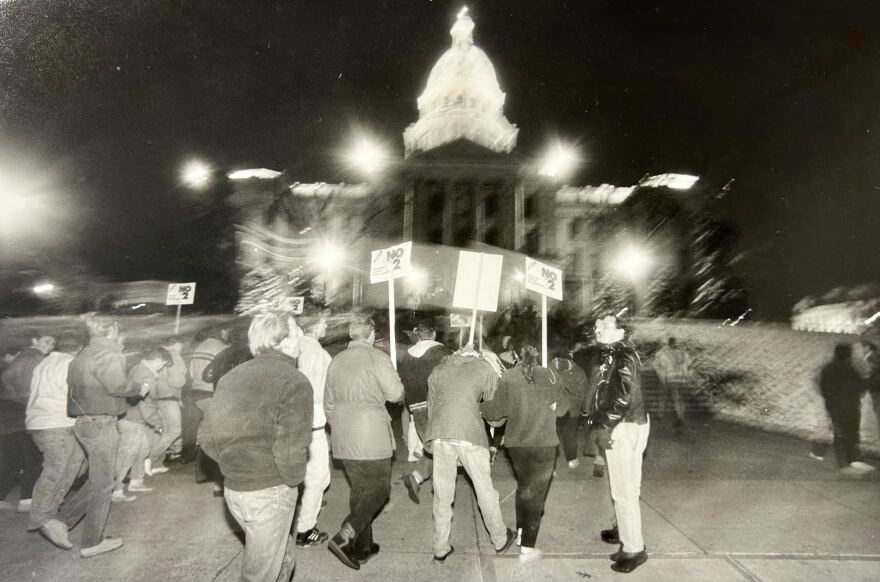

Colorado voters passed an anti-gay state law called Amendment 2. It repealed anti-discrimination ordinances passed by Boulder, Aspen and Denver, blocked future protections and earned the state an unenviable nickname: The Hate State.

But it also sparked a landmark legal battle and changed the lives of thousands of gay Coloradans.

“The Amendment 2 decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1996 will certainly go down as the Supreme Court decision that changed how LGBT people were talked about. It was a sea change,” Russell said.

But how did a state that today is celebrated as one of the most friendly in the country for LGBTQ+ people, and led by the first openly gay governor, once earn itself a reputation as one of the least friendly?

Part of the answer lies in an old video cassette tape that landed in Colorado in the months before the vote over Amendment 2.

The ‘Gay Agenda’

In the weeks before the vote for Amendment 2 in the fall of 1992, a videotape began making its way around the churches of Colorado. It was called, The Gay Agenda.

The tape uses ominous music and unnamed studies. One line alleged without citing any evidence that “male homosexuals average between 20 and 106 partners a year.”

The video also claimed gay people were politically devious, plotting special laws to get special rights. More than 4,000 copies of the VHS tape circulated around Colorado, from a church in Steamboat Springs to a college Republican meeting in Golden.

When Glenda Russell heard this video, she was alarmed.

“Outright lies, lots of distortion,” she said of what was on the tape.

And she grew concerned about the upcoming vote on Amendment 2.

“And I thought we're going to lose this election and we're going to lose it because this really is garden-variety American homophobia. And this is going to be easy for the campaign promoting Amendment 2 to tap into.”

Amendment 2 prohibited communities and the State of Colorado from protecting gay people with anti-discrimination ordinances. It essentially sanctioned discrimination against gay people. It would be okay to be fired from a job because of sexuality, or be denied housing. And a man named Will Perkins would be the one to tap into films like The Gay Agenda to get it passed.

The spokesperson

Will Perkins was so famous in Colorado in the 1990s, archivists from History Colorado, the state history museum, paid him a visit to record his memories about Amendment 2 while they were fresh.

Perkins was a car dealer and a leading member of a group called Coloradans for Family Values, who was coordinating the ground game to pass Amendment 2.

“I never ran into anybody that said ‘I hate homosexuals. Where do I sign it?,’ Perkins said in 1996 as he reflected on his attempts to gather signatures to get Amendment 2 on the ballot. “ It was a matter of special, privileged position based on how they had sex for whatever reason.”

When the committee began its signature drive, Perkins famously collected more than one thousand of them himself.

There also was a piece of anti-gay propaganda printed and passed to thousands of homes before election day. As part of Perkins’ and the committee’s media strategy, they produced an 8-page tabloid newspaper to convince voters to support the Amendment.

“The tabloid was, was instrumental because it was something that anyone that was interested could sit down and certainly see from our perspective what, what the issues were and, and how to vote,” he said.

The same kinds of propaganda and themes used in The Gay Agenda film, were now in print.

And the decision to print the paper would be revisited a few years later when the fate of Amendment 2 went to the United States Supreme Court.

Time to vote

In November 1992, it was time to vote. Coloradans went to the polls to decide the race between Bill Clinton and George H.W. Bush as well as the fate of Amendment 2. As the polls closed, Glenda drove down to Pueblo to attend what was initially billed as a party to celebrate the defeat of Amendment 2.

“As more and more numbers came in, it was clear that Amendment 2 was going to pass. And, I was, I was sort of a little stunned, not surprised,” Russell said.

The anti-gay measure passed with 53%t of the vote.

“ I remember seeing a man I knew whom I respected, who was crying. And I just thought, oh, this is going to be going all over the place,” Russell recalled.

For Will Perkins in Colorado Springs, it was a good night. He invited supporters into his car dealership for the watch party.

“I didn't get to bed till about 3 in the morning. We said, ‘well, our job's done’. It was a great night,” he said in an oral history interview.

But when the election results were final the next morning, many residents were shocked and outraged.

Letters started pouring into the newsroom at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver. Almost all of them were critical of the election results.

Frank Berndt of Boulder called Amendment 2 supporters bigots.

Donna Garcia of Aurora wrote she was shocked, appalled and angry.

“I guess we don’t really believe in liberty and justice for all,” she wrote.

Something disturbing

Glenda had started her career as a psychologist at the time. She started noticing something disturbing when she saw her first clients in her psychotherapy office immediately after the election.

“My first client of the day was a lesbian woman who was talking about her concerns in her relationship with her with another woman, and the concerns around how out were they going to be in the aftermath of this, of this election,” Russell said. “My second client of the day was a straight guy who was tearfully talking about his concern for a gay friend of his who had been really impacted by the election. And I sat there and I said to myself, somebody has got to figure out what is going on here.”

So Glenda started a study that would become the first time in America someone had set out to understand how a ballot measure targeting LGBTQ+ people affected them psychologically.

She sent a questionnaire to queer Coloradans asking what impact the election had on their mental health.

Many responded they were experiencing anxiety and depression. Russell said the most profound responses came in an open ended part of the survey.

“A lot of grief, a lot of shock, a lot of anger, a lot of 'I'm going to go in the closet, I'm coming out of the closet.' A lot of fear,” she said.

And lots of people who said they were leaving the state.

“I know at least a half a dozen people who moved out of Colorado and said, 'I can't tolerate this. I can't live in this. And with people talking about me this way.'”

She recalls queer residents would fret about their safety while sitting at stoplights after the election.

"People would say, ‘I was sitting at the stoplight, and I was looking to the car on the right of me, and I looked at the car on the left of me, and I thought, did you vote for Amendment 2?' In the sense of how can I be safe here?

A state of mourning

Once Amendment 2 was a reality, many gay Coloradans went into a state of mourning.

“It passed and we all went into collective mourning,” he said. “That could happen here?," said Larry Brown, a Rainbow elder in Boulder County.

But they also started planning a movement.

Brown felt this pain. But he didn’t leave. He was bewildered and angry, and he thought about it.

“I think there's fight or flight, you know,” Brownld said. “Can you fight this? No, it's already passed.”

Brown already knew hate. Where he grew up in southern New Mexico, being open about his sexuality wasn’t an option.

“It was a totally closeted world,” he said. “And, you were taking your life in your hands if you came out, frankly, in employment in day to day activities. Just everything about it. It was, you kept things under wraps.”

When Amendment 2 passed and gay people were vilified by a political campaign, Brown and thousands of other LGBTQ+ people around the country chose to fight. Brown became active. He became proud. Amendment 2, helped him find community, and he would eventually find more community with a group called the Rainbow Elders in Boulder County, where he serves as a role model for younger LGBTQ people.

Amendment 2 was a wake up call.

The Hate State

Soon, Colorado had its moniker – The Hate State.

Celebrities including Barbara Streisand called for people to boycott the state because “the moral climate there is no longer acceptable.”

CBS News reported that Amendment 2 cost Colorado more than $38 million in lost conventions alone.

“The Hate State is just such a large, damning, moniker,” Brown said. “We wore it and we bore it.”

After it was approved by voters on November 3, 1992, Brown and other Coloradans found themselves looking to the legal system, hoping it would declare Amendment 2 unconstitutional.

And it didn’t take long for the epic legal battle to begin.

Ready to go

Amendment 2 was challenged by gay men, lesbians, and the cities that had enacted anti-discrimination ordinances.

To win their case in court, they turned to Jean Dubofsky.

Dubofsky already was well known in Colorado. At age 37, in 1979, she was appointed to the Colorado Supreme Court. She was the court’s first woman, where she served until 1987, when she went into private practice. A few years later, this case, Romer vs. Evans, put her in the spotlight.

But she wasn’t alone.

"And I had, it turned out to be a cast of thousands,” she told the Carnegie Library for Local History in Boulder in 2008. “We laughed about it because I've never had too many volunteers for anything in my entire life. All over the country, people were calling, what can we do to help?

One of the first things Dubofsky did to prepare was conduct research on the committee and the origins of Amendment 2. Her research helps answer the question – how did this come about?

“We put on evidence that explained that these various, mostly far-right religious groups, had begun an anti-gay rights effort after communism basically went away, which was in the late 1980s, and they lost anti-communism as a means of raising money,” Dubofsky said.She found that the people behind the amendment came to Colorado Springs from southern California to work at a 57-acre business development for religious organizations. The ‘Hate State’ amendment, she says, was really about fundraising.

“Colorado had almost no law that protected, gay men and lesbians from discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation,” she said. “But the religious organizations said that there was a gay rights agenda and that it needed to be blocked in Colorado.”

Dobofsky and the attorneys primarily argued that gay people deserved equal protection under the 14th Amendment – attacking the idea that the government was creating new rights for gays and lesbians.

She won the trial in Denver District Court, she prevailed in the Colorado Supreme Court, and to no one’s surprise, the case eventually was taken up by the Supreme Court of the United States.

“The Supreme Court had more requests for passes to get into that argument than they ever had for any case in the court's history,” she said.

Dubofsky says her favorite moment of the case came on October 10, 1995 , when she tangled with the often combative conservative associate justice, Antonin Scalia. Scalia tried to trip Dubofsky up over legal citations, but Dubofsky was prepared.

The SCOTUS decision was announced on May 20, 1996.

Dubofsky got the call from the court at 8 a.m. on that Monday, learning she won the case.

“And I just gasp, I couldn't believe it,” she recalled.

In the ruling, the Court wrote that Amendment 2, “classifies homosexuals not to serve a legislative end – but to make them unequal to everyone else.”

The so-called Hate State Amendment was dead.

Bending toward justice

Back in her research room, Psychologist Glenda Russell says the case helped spread awareness about gay people and served as a foundation for future legal victories.

“All of the decisions that have been sort of supportive of LGBT people since then really come from that decision in Romer,” she said. “And that's one of the reasons it's so incredibly important.”

Russell said the Amendment 2 saga also affected queer Coloradans in very personal ways.

“We really can and often do learn from the hardest things that happen to us,” she said. “We learned because people came out of the closet, they met other gay people.”

But the fight for equality hasn’t ended in Colorado, or beyond. Russell points to anti-LGBTQ+ bills being sponsored in dozens of states as a reason to remember Colorado’s history.

“The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” she said. “We have to step back and see that whole arc. If we don't see how that whole arc, every one of these events feels like it's overwhelming, it's overpowering. It's going to stop us in our tracks. We're never going to be able to move forward. But that's not true.”

-----

Next Episode

The number of Pride celebrations are growing across Northern Colorado but in some communities it's still a struggle to hold these events. This includes in Weld County where a local librarian - and their friends - took over organizing Greeley Pride after it was cancelled.

The Colorado Dream: “Ending the Hate State" is a production from KUNC News and a member of the NPR Podcast Network.